East Hetton Pit, Kelloe, County Durham

I was born in Kelloe in 1961, a mining village sitting about eight miles south east of Durham City. This was my home until I left for `University in 1979 thanks to a solid education at Spennymoor Secondary School which had managed to retain its rigorous but rather old fashioned Grammar School ethos when I arrived in 1972. It was a solid but rather unadventurous education that has probably served me well. It certainly instilled in me much of my ‘addiction’ to the protestant work ethic and, perhaps, an overdeveloped sense of duty.

My Father and many of his family were miners or pitman. He was send down the village pit at the age of 15 or 16 and there he stayed until the mine closed in 1983. From there he travelled to Easington before retirement in his mid 50s or so. It was dangerous work with shifts that disrupted family life. Coal is in my roots and bones though like many of my contemporaries at education took me away into a very different world. We never had very much in those days but it was a happy and secure childhood with my brother and two sisters. It was a world so very different as I look back but one of which I am proud. I am a Durham lad. I am a pitmans Son.

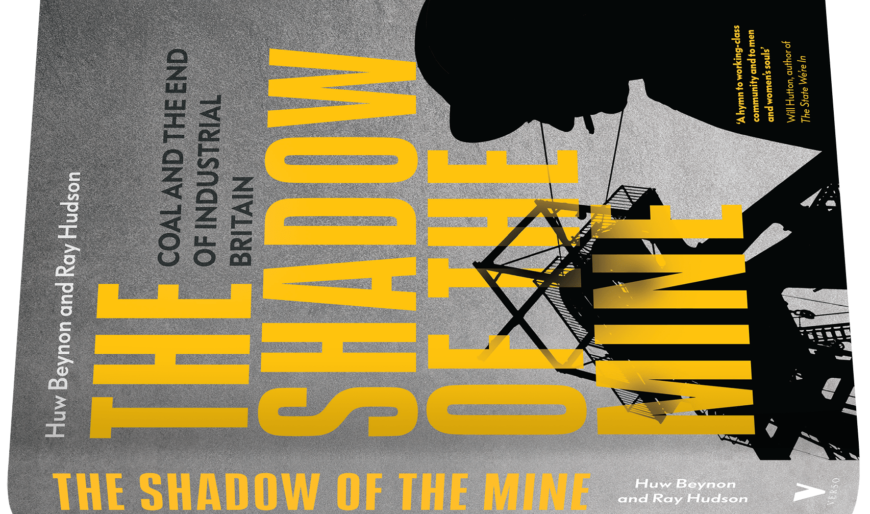

This may go some way to explaining why this book has helped me think a bit more deeply about my roots and the things that have shaped and perplexed me. I was grateful to Nick Holtam, the former Bishop of Salisbury and Trustee of Sarum College for gifting me with this book

I read it quickly and have kept it on my shelves next to Jeremy Paxman’s book Black Gold: The History of How Coal Made Britain published in 2021. I have had reason to read it again this summer perhaps relating to the second anniversary of my Fathers death. Geography does change with the loss of the parental home. Memories seem stronger and sometimes stronger !

The Durham Miners Gala still continues every July though the mines have long since closed. The site of the pit in my home village is now landscaped erasing any physical memory of what went on above and below ground. The Gala is deeply bound up with the Labour movement and its commitment to solidarity and collectivism. This sometimes seems so marginal to the labour movement today. As industry changes so does politics but we might be a wiser political ecology if we balanced economic stability with the values of equality and fairness in the way society organises itself for our common good. We abandon the values of the working classes at our peril !

This carefully researched narrative tells that story of the spirit of coal and its life as well as how deep social betrayal lasts within memory and new political opportunist choices. Benyon and Hudson show their readers how to tell a story and ensure that listening to others through meticulous research may help the reader position themselves within their social, political and economic narratives. At the heart of this for this Durham lad is class and the way successive political choices have shaped the distribution of wealth. It is uneasy reading to learn of the huge profits from coal ( not always shared with the miners) and the journey to post industrial devastation.

The election of Margaret Thatcher in 1979 is a key moment for the prospects of coal. These were the days of stockpiling at power stations, coal imports, social security cuts and police protection for strikebreakers. All were planned in minute detail. While the coalfields were promised “regeneration”, but “inward investment” these came in the form of low-paid, low-skilled private sector jobs. Pit communities were left to rot. I saw this at first hand while I was a theological student in Cambridge training for ministry.

David Jenkins, the then Bishop of Durham. spoke out with ethical clarity about what he saw happening in communities and in economic systems. Beynon and Hudson remind us of the material realities that cemented the perception that globalisation would only benefit a select few. We seem unclear about the role of the state is and, within that, what public ownership is, could be and should be.

It may be the case that the deeper story of a disenfranchised working class explains the decline of Labour’s vote and possibly its present identity crisis that has allowed alternative visions of society to emerge. We seem to be better at creating a society of passive consumers rather than active citizens. The market has much to answer for !

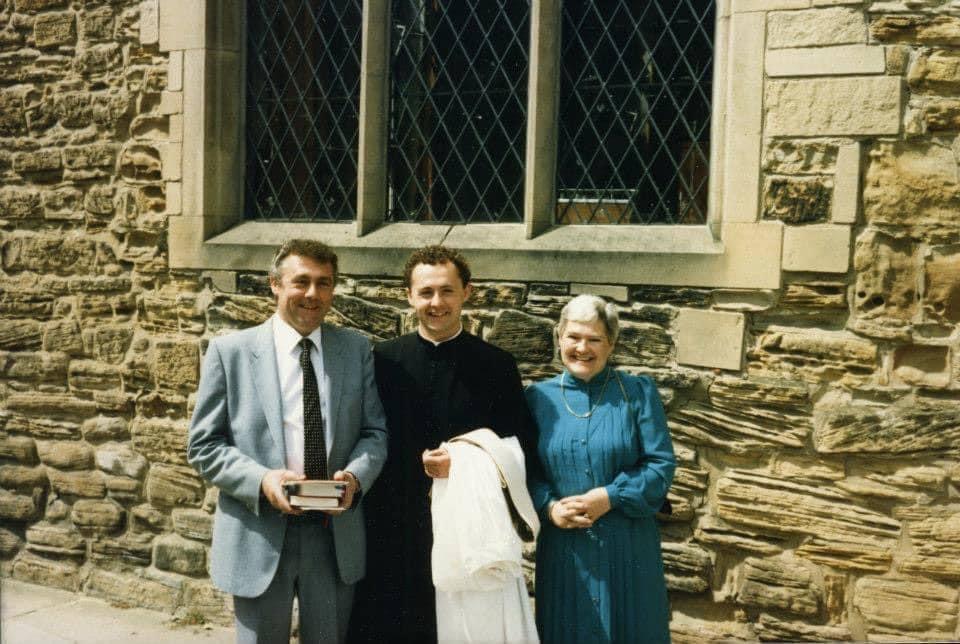

This year I was ordained in 1985 in Durham Cathedral. They were different times for the North East and the Church of England. I was younger and full of ideals. I believe in people and their innate goodness. I am blessed with a good dose of Durham pragmatism combined with some impatience that does not always temper my judgement. I am a proud miners son and this book is a reminder of the importance of telling that story from a range of social, economic and political perspectives.

I take my inspiration from David Jenkins. Jenkins sought to lift people’s sights above issues of mere historical factuality to truths “far more important than that” — truths that go to the heart of what it means to be human beings fully alive and thereby glorifying God. This is why Jenkins was such an effective public theologian. Long before the terms “applied theology” and “contextual theology” became commonplace, Jenkins was applying theology and contextualising it in ways that shed the Light of Christ on socio-economic and political issues with courage and conviction. He cared about the communities of County Durham and saw the effects of the orchestrated decline of the coal industry. His theology was difficult to systemise, but might be summarised as bottom up, freed up, joined up, and down to earth. This Durham tradition has inspired me over four decades.

Can the Churches take up the challenge to get out into the communities they seek to serve, organise social support to build solidarity and nuture a radical kindness ? It might need a shift in its priorities and a deeper and more radical theology that can embrace those on the edges?